Two weeks ago, I had to self-isolate for a week over some mild symptoms.

Just prior to this, I’d been working on some exciting ideas and making good progress in my free time after work.

Thankfully, my symptoms improved after a couple of days and I thought to myself, “Great! I can use the rest of this period to get ahead on that project”.

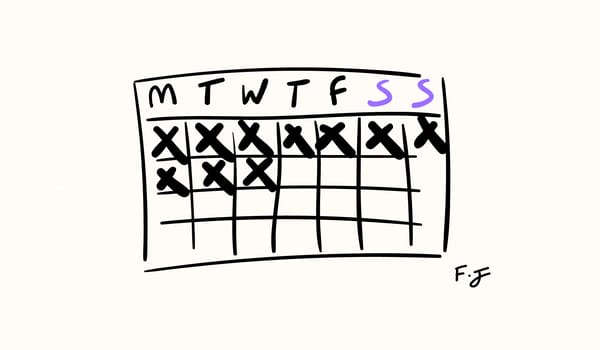

Instead, I found the following days waking up at 11 am, spending hours on Youtube in my PJs, planting myself into a corner of my garden (won’t apologise for this) and finishing the day watching 3+ hours of Money Heist on Netflix.

It brought some thoughts on productivity and routine back to the forefront of my mind, and if you’re anything like the average person, you might relate to this too.

Why We Need Routine

Blessed with several days of uninterrupted isolation in my room, the loss of a fixed routine highlighted the true extent of my uselessness.

I hate to admit it, but without the routine, I was a disorganised mess.

Conversely then, a ‘routine’ must have been doing a lot of the work for me!

More importantly, let’s talk about the routines that we don’t much of a say in. For example, our jobs. Yes, we choose them ourselves, but we (for the most part) don’t get a say in the hours we work, where we have to do that work and when we can take allocated breaks. Let’s call this an ‘external routine’, one that’s imposed on us and difficult to escape without some consequences.

On my days of isolation, if I managed to wake up at 7am, get some solid work done before 5pm, eat at allocated times and enjoy my evening before a sensible bed-time, it would only have been due to an internal drive to ensure good routine. Let’s call this an ‘internal routine’, one we impose on ourselves with the help of productive habitual behaviour and commendable self-control (I’m still working on that).

“Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion” — Parkinson’s law

Now, a routine does two important things:

Allocate time. Allocating different periods of the day to certain tasks trains the brain to identify that it won’t have any other time to do it, meaning it’ll quickly switch into the right gear when it’s time to.When I get home from work, I know I won’t get the chance to work on my side-projects until the same time next day, which gives me the kick I need to get things done, there and then.

Reduce time per activity. Instead of spreading out tasks over a whole day, giving yourself a smaller amount of time to do so creates a sense of urgency and scarcity of time.If you’ve ever had 5% battery left on your phone to get something done (and no charger), that was probably the most productive you’ve ever been on that phone!

What’s strange is that I was getting more work done in my evenings post-work than I was in a whole day of isolated freedom.

Given that I’m not lucky enough to have any free time to work on side-projects during my work shifts, despite ‘losing’ 9–13 hours of my day at work (where I don’t have any free time to work on these side-projects) I was still getting more work done!

That’s the power of routine.

Setting Rules To Get Things Done

Over the last few years, I’ve discovered something about myself which has helped me get more things done, and it’s helped some of the biggest productivity wizards too…

I can’t trust myself.

I can’t trust myself to ignore my phone when it’s within arms reach.I can’t trust myself to ignore emails when a new notification just came in.I can’t trust myself to finish my essay when Youtube is just one click away.

I’d think to myself, “why do people have all these rules and hacks for getting things done, can’t they just do it if it’s that important to them? Perhaps they’re weak-minded. That could never be me, just watch!”

Although I’d still like to believe that I can eventually develop the self-constraint to stick with the important and ignore the distracting on-command, I’ve come to accept that I fail. A lot.

The truth is, creating rules and ‘hacks’ that allow us to be more productive work so well because they trick us. And we have to be tricked, because we can’t be trusted.

The best way to demonstrate this is to provide some context through common examples:

Hiding our phones from ourselves whilst working.This works because we’re too weak to resist picking up our phones if it's nearby. By throwing it to the other corner of the room, we tell ourselves, “I know you want the phone to be easily accessible, but you can’t have it”.

Having a ‘work’ area and a ‘chill’ area.Some people commit their desk to be solely used for productive work. When they want to watch videos or do some online shopping, they might sit on their bed or a sofa, training their brains to associate sitting at the desk with getting important work done.This is our way of telling our brains “You think you’ve got enough self-control to do both activities at the desk appropriately, but you can’t, so I have to condition you. Desk = Work. Bed = Chill.”

Although we may not realise it, some of our most productive work sessions have been influenced by some sort of rules/regulations we’ve imposed on ourselves, knowingly or unknowingly.

My personal favourite has been occasionally leaving my (previous) laptop charger behind whilst working away from home. Knowing this, I had imposed a self-inflicted time-bomb of 5 hours before my laptop would die.

This way, I’d removed the opportunity to procrastinate and restricted myself to just 5 hours at any coffee shop or workspace, leaving the rest of my day open to my other plans.

During medical school, I began to listen to classical music whilst revising (thanks Ludovico Einaudi), a genre I wouldn’t usually listen to for any other situation. Before I knew it, playing classical music would almost instantly put me in working mode.

I’d unknowingly conditioned my brain to associate classical music with studying!

Allow Yourself To Be Told What To Do

Here’s the crux of this article: Sometimes we have to impose rules and routine on ourselves in order to get things done.

The eureka moment comes after the realisation that despite wanting to be super-efficient on our own, we’re actually pretty useless if we depend on our own ‘internal’ routines.

Therefore, by holding ourselves accountable publicly, socially and financially, we bypass the need for possessing the necessary self-motivation.

If you’ve identified that something needs to be done, consider creating some ‘external’ rules and routines that are difficult to break.

For example, if you’d like to only spend a portion of your day checking email, you could restrict your email applications to only refresh at certain times of the day, or, you could even set an autoresponder to inform people that you’ll only be replying at said time of day.

The first method prevents us from seeing constant notifications of incoming mail. The second method ensures that you don’t feel anxious about not-replying promptly, considering that everyone who’s emailed you has been made aware that you’ll be replying later on.

Social accountability is incredibly powerful, too.

If I missed this weekly newsletter, people may think I’m a failure who couldn’t keep up a newsletter for more than 10 weeks (yes, I’ve surprised myself too 🎉).

That’s part of why I advertise this as a weekly newsletter. If I didn’t, I wouldn't feel guilty about missing a week, a month, perhaps even giving up entirely. I’ve created an ‘external’ routine, one that relies on social accountability to keep me going.

The most ‘productive’ and ‘disciplined’ people we aspire to emulate aren’t as self-reliant as we think. They’ve simply identified early on that they’re incapable of becoming productivity machines without external influences.

Look carefully at their average day, and you’ll notice widespread use of psychological productivity ‘hacks’, social accountability and ‘external’ routines that regulate their actions and behaviours.

Sometimes, we have to seek external motivations. It might be the only thing that helps us get it done.

🤩P.S: About those exciting new projects I mentioned at the start, it may or may not be something to do with this link (Go on… click it).

💡If you liked this article, you might like this one too: Get Out of the Fast Lane

💬 Let me know your thoughts and if you enjoyed the article, please drop a ❤️!

✏️ About the Author:

👨🏽⚕️Faisal is a Junior Doctor working in the NHS and the founder of YoungAcademics.

📲If you enjoyed this edition, consider forwarding this email to a friend.

💌If you’ve been sent here by a friend, join the tribe and have these weekly reads sent to your inbox (free). Subscribe here 🚀